In 1968, the Fair Housing Act was signed by the U.S. government in order to create a less segregated environment for racial minorities, especially the African Americans. President Lyndon B. Johnson claimed that black people would no longer suffer from humiliation in residence because of their race. Today, a half century after the Fair Housing Act became a civil-rights landmark, this statement becomes a sarcastic remark. There are multiple studies showing that African Americans are still highly segregated from the Whites, in either housing or education segregation. “We still have a very, very segregated society, in terms of housing and schools,” John R. Logan, a Brown University sociology professor who specializes in housing discrimination, comments on present situations. A segregated community tends to give the African Americans less opportunity to assimilate in a majority community where they are able to require better resources and life quality. More importantly, the move from “segregation” to “integration” implies that the American society is involving more racial equality.

New York has the fourth-highest level of residential segregation in America. In a survey of 50 major metropolitan areas, segregation in New York was discovered to have lasting effects, since the neighborhoods would significantly affect the living population. New York neighborhoods with minorities comprising at least 75 percent of the population were have a median income that is 20 percent less than the metro-wide median. New York’s overall segregation index is 0.58, just behind Milwaukee, which is the most segregated place in the country with an index of 0.61.

This is a map of housing segregation in New York. The blue regions imply a residential pattern of African Americans, while the green regions are the Whites. It is clear to see that most of the Whites live in Manhattan, and majorities of African Americans are segregated in district such as Brooklyn and Harlem. These evidence suggest that an integrated New York still has a long way to go.

A study interprets that financial capital and human capital are two essential indexes for a racial minority group to assimilate into majority community. With higher income and better education level, a non-white person is able to have more upward mobility and move out from a segregated community. However, the African Americans in New York are suffering from both economic and education segregations.

The study shows that decline in residential segregation is associated with more income parity and metropolitan areas with higher proportions of college-educated Puerto Ricans would experience lower residential segregation levels as well. Researchers discover that the residential patterns of Chinese in New York are related to socioeconomic status. That is, the Chinese are more likely to live outside of Manhattan and outside the city itself if they have higher socioeconomic status. Those with lower socioeconomic status are more willingly to live in a segregated community. There exists an advantage in wages for those living in integrated areas over those living in segregated areas. Thus, there is a strong connection between collective levels of human and financial capital and spatial assimilation.

Why the African Americans in New York endure these various forms of segregation, and the situation still exists even in today? How the U.S. government plays a role in improving the segregated phenomenon? Are their policies efficiently solving the segregation problems? Or they just intensify the segregation? Previous studies on residential segregation have hardly answered the question of how policy matters to segregation. It is tempting to say that policies do contain racism factors where the Whites are given priority over other racial minority groups. Either federal policies like redlining in past or local zoning laws in present-day continuously drive residential segregation in the United States. Under President Obama, the Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2015 required states and cities to detect how their housing policies affected segregation. But the Trump administration stalled that effort.

In line with those data, did government policies intensify African Americans’ residential segregation in New York under impacts of racism? The answer is obviously yes. According to the critical race theory, racism is deeply embedded and normalized in American society with identifications that power structures in the society are based on white privilege and white supremacy, which perpetuates the marginalization of racial minorities. On historical context, black people were initially categorized as a commodity rather than as people and this notion is embedded in American society even after slavery repeal. Black people continue to fight for their rights in this country but racism is still deeply rooted in the American society. Slavery shaped the early housing options for blacks. Over time, as slavery was replaced by institutional and economic forces that limited African American participation in civic and community life, their housing choices followed a pattern of inequality in keeping with their status in the nation.

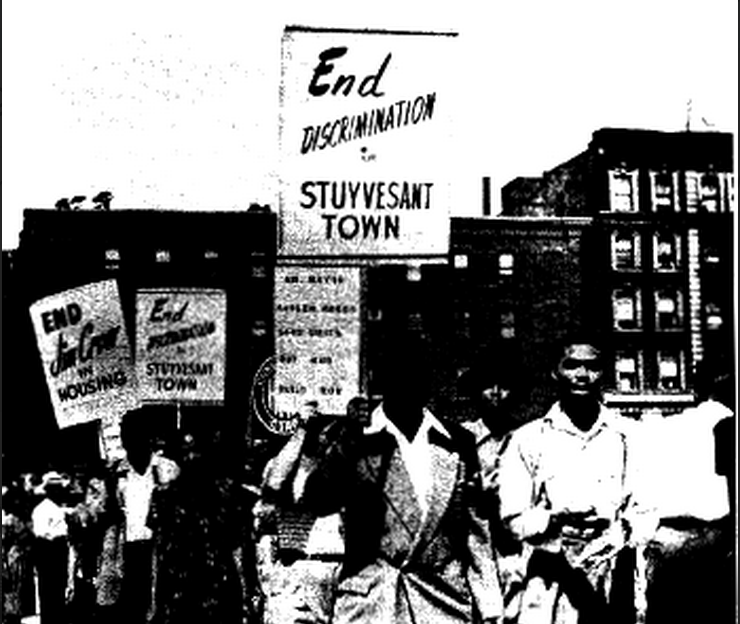

Beginning from 1876, Jim Crow laws that endorsed to legalize racial segregation spread throughout the South. Black people in New York suffered from written and unwritten rules against racial mixing in marriage, public accommodations and housing. In 1938, the State legislature in New York amended its insurance code to permit the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to build large housing projects such as first Parkchester in the Bronx and Stuyvesant Town in Manhattan “for white people only.” New York government granted substantial tax concessions for Stuyvesant Town, even after MetLife’s chairman testified that the project would exclude black families because “Negroes and whites don’t mix” . The building of the suburbs intensified segregation in New York city to a further extent. After World War Ⅱ, Robert Moses, the city’s Master Builder, planned for the sprawling highways and the commercialization of the automobile allowed for the suburbs of New York to be settled by the wealthier white families. This urban planning led to the White Flight as white families began to flee from the deteriorating urban sprawl, leaving the African Americans in the urban district.

In the period around the middle of the 20th century, housing discrimination was a feature of local, state, and federal policy. Such discriminated policies produced federal housing programs that “pushed” African Americans into highly segregated ghettoes. Encouraged by the federal government, lenders employed underwriting rules that preferred and sought to maintain racially white neighborhoods. Federal agencies financed nearly half of all suburban homes in the 1950s and 1960s, boosting homeownership rates from nearly 30% of the population to more than 60% by 1960. But this subsidize only brought benefits to middle-class households, leaving the African Americans, who are mostly low-income groups behind. According to analysis, 98% of the loans approved by the federal government between 1934 and 1968 went to white applicants. Discrimination in housing and lending practices undoubtedly bring hypersegregation of black Americans in urban communities.

The critical race theory of “white priority and white supremacy” has merged in New York government decisions and promoted segregation. But this is not the end of the story. Racism also induces policy failure in shortening income gap between African Americans and Whites and facilitating the assimilation process. Through the first half of the 20th century, the federal government actively excluded black people from government wealth-building programs. In the 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal helped to build a solid middle class through social programs such as Social Security and the minimum wage. But most of black people, in occupations of agricultural laborers or domestic workers, were ineligible for these benefits. In 1933, the establishment of the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) helped to save the collapsing housing market, but it largely excluded black neighborhoods from government-insured loans.

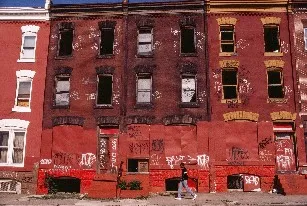

Those neighborhoods were regarded as “hazardous” and colored in red on maps, which is a practice known as “redlining”. Redlining is a tactic denying people of color, especially Black people, access to mortgage refinancing and federal underwriting opportunities. It criticizes that residents of color were financially risky and a threat to local property values. Only 2% of the $120 billion in federal government loans distributed between 1934 and 1962 went to non-white families. According to Richard Rothstein, “Federal and state bank regulators approved and encouraged ‘redlining’ policies, banning loans to black families in white suburbs and even, in most cases, to black families in black neighborhoods, leading to those neighborhoods’ deterioration and ghettoization.” As a result, the government-encouraged redlining keeps New York segregated. Many black neighborhoods with low income become concentrated in those areas creating not only racial segregation but also economic segregation.

The impact of policy racism extends to even today. Approximately 74 percent of neighborhoods that the HOLC deemed “hazardous” in the 1930s remain low to moderate income, and more than 60% are predominantly non-white. While federal intervention and investment supported expansions of homeownership and affordable housing for countless white families, it has undermined wealth building in black communities. “The major way in which people have an opportunity to accumulate wealth is contingent on the wealth positions of their parents and their grandparents. To the extent that blacks have the capacity to accumulate wealth, we have not had the ability to transfer the same kinds of resources across generations”. Reporters from Syracuse.com demonstrate that homeowners in low income, predominantly minority neighborhoods in Syracuse have been paying higher property taxes than they lawfully should. This is due to the property reassessment since 1966. Over the past few decades market values of homes in white neighborhoods have risen much more than market values of homes in black ones. As a result, homeowners in white neighborhoods have tax assessments that are too low compared with the value of their homes. These homeowners would pay a smaller share of the total city tax bill than they should. Homeowners in low-income racial minorities, relatively, are paying a higher share than they should. In New York City, rich neighborhoods pay into the same municipal property tax fund as poor neighborhoods. With a such high tax payment, how much income is left for the African Americans?

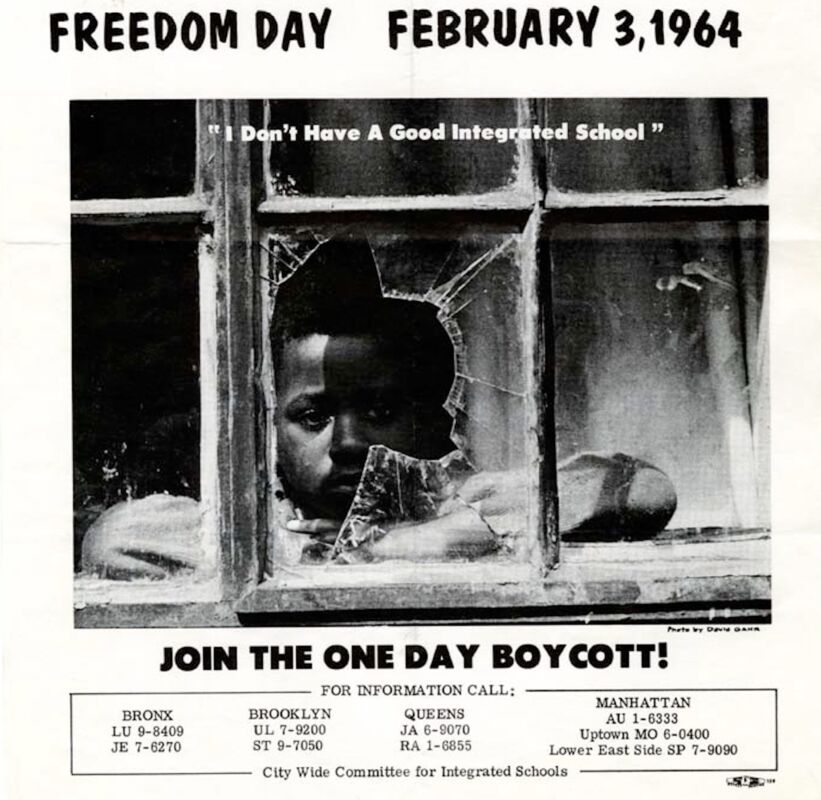

Beyond income wealth, school segregation has remained severely high across the state. In 1954, the Brown vs. Board of Education case led the Board of Regents and the New York State Department of Education to desegregate and integrate New York’s school systems. However, the failure of New York City’s school board to keep its promise and integrate a single school in Harlem led to the school decentralization movement. This broke the city up into more than 30 school districts, in hope that local control would produce educational breakthroughs, but it left inequality largely untouched. During the 1960s, debate over racial integration began to arise in a number of Long Island school districts. There were many voices against racial segregation but the government did not implement a plan. In Hempstead, an interdistrict merger with majority-white and neighboring districts of Garden City and Uniondale was proposed but failed.

Taking case in the South Bronx, the district is highly segregated due to mismanaged government housing projects and failure of urban renewal policy. District 7 in South Bronx, which is the worst performing school district in New York, consists mostly black and Latino students. Reports show that an average of 21.3% of students in grades 3-8 performing below the standard average. Across the board, average test scores fall below the state median in all subjects and the pass rate on all tests averages 29.3%, which is far below acceptable performance from a school. Such low performances in grades indicate a low human capital index in Bronx, giving the African Americans less upward mobility and opportunity to assimilate in the majority community.

Racism in school choice policies that give priorities to whites or high-income family for entering high-performing schools aggregates education segregation. In middle and high schools, the school choice policies tend to perpetuate racial segregation across the city. The government implemented middle-school choice program is a selective one, with schools screening applicants based on different criteria. This competitive selection process allows schools to disfavor black students who are not high achieving or who have behavior problems. In such a case, the African American students can hardly have a chance to enter high-performing schools. Bloomberg’s 2004 universal school-choice policy for high schools allows all students to engage in the process of choosing a school, with each school using an admission method to evaluate applicants. Similar to the middle-school choice policy, the city’s high school choice policy process tends to work better for advantaged families which are mostly white families with high income. Two districts in the city, CSD 2 and 26, also use intra-district preferences for their high school admission, preventing many African American students from attending their schools. The school choice policies restrict African American’s liberty in pursuing better education resources. Most of the families in whites community refuse to send their kids to a “segregated” school involving racial minorities in majority, making the assimilation process more difficult.

There is an urged call for changes in government policies by bringing more equality in policy decisions. Government subsidize should help those low-income African Americans by offering more affordable housings. The New York government agencies need to lower rental price in a less segregated community. Moreover, policymakers should eliminate the concept of “white supremacy” before carrying out their decisions. They can implement policies such as rezoning the New York cities or reducing tax rates for low-income groups. Last but not least, it is necessary to locate those affordable houses near regions with more job opportunity, reducing economic segregation in African Americans. reducing racial isolation, promoting diverse schools, and ensuring an equal distribution of resources. Such policies should address how agencies can create student assignment and choice policies that foster diverse schools, discuss how to recruit a diverse teaching staff. The consequence of new education policies should provide a framework for supporting intra and interdistrict or universal programs and reinforce a commitment to achieving racial and economic diversity. Furthermore, because housing and school segregation are highly correlated, local fair housing organizations should monitor land use and zoning decisions in advocating low-income housing to be built in communities near high-performing schools.

The case of African Americans’ residential segregation in New York only pictures a small portion in the big nation. There are far more black people suffering from segregation due to racial inequality in government policy in today’s USA. Government decisions play an essential role in leading to these consequences. This is not a story only for African Americans but also for other racial minorities such as Asians and Hispanics. As a home to a population that speaks over 200 languages, involves 37% foreign-born New Yorkers, and owns 50% immigrant businesses, New York has urgent responsibilities to boost diversity integration. If New York can’t, then who else can?